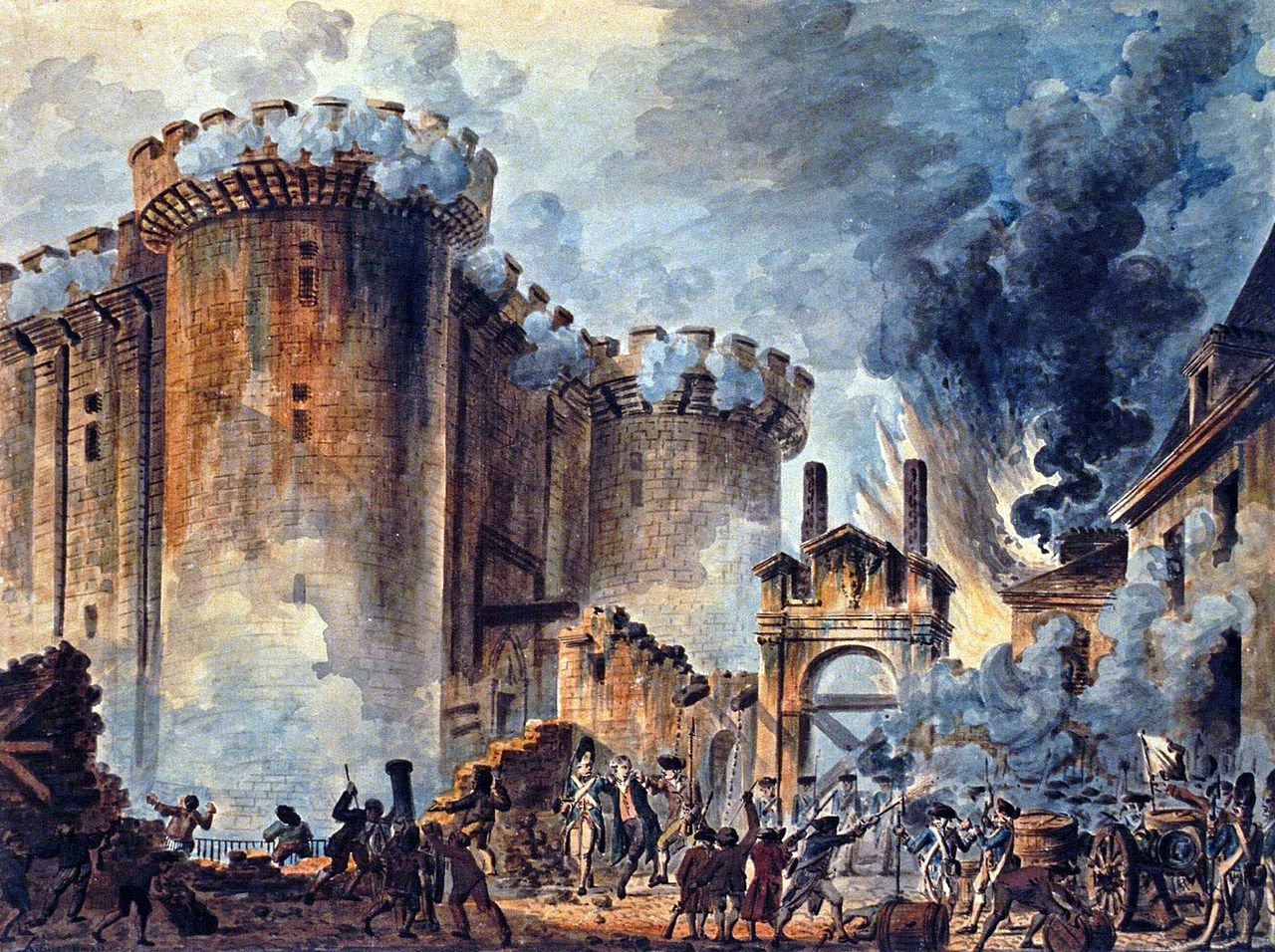

Bastille Day was last week. I have a soft spot for the French Revolution in my heart, being torn between the Jacobins and the Hebertists on different days myself. But re-reading all about the Revolution of 1789 has reminded me of a dark truth: rebellion, revolution, and insurrection are the children of want, not of political need.

While it's true that somebody always hates the king, they rarely have the power to upset the political order in the every day course of events. True, they may plan a long coup, build up power to launch a rebellion composed of their loyal vassalmen, but there is always a trigger. The weakness of the social order must be made manifest in some way before the trap can be sprung. The iron, as they say, must be hot.

Political insurrection of that type must gravitate toward a legitimate or semi-legitimate figure of power. This is why people like princes of the blood, uncles, aunts, sisters, brothers, or other such relationships are so dangerous in a monarchic semi-feudal land. They represent poles of power with at least the patina of legitimacy. If you're going to kill the king, you can't very well sit on his throne and say, "Well, now I'm the king," no matter what Game of Thrones tells you. You need to have some claim at legitimacy going for you, even if it's hilariously attenuated.

The kind of revolutions we're talking about today, however, don't occur in such a planned manner. The revolution, for example, depicted in The Hunger Games is one that's really organized and fed by a shadow society for decades. That doesn't happen. What happens is that ideologues exist and foment their malcontent, but the people fail to rise up. They write angry pamphlets and letters, they preach in the streets, they preach from the pulpits, whatever they do, but the people don't follow them.

Until food is hard to come by.

When food prices start to rise, the social order begins to crumble. People really care about being able to afford to eat. Famine and plague are great ways to mobilize an angry populous. Tax riots occur not when the taxes increase, but when the ability to feed families is reduced. The price of wheat in the Paris commune went from 50% of a worker's wage to 80% in the course of a month. That kind of inflation is what causes men to go mad. Women too.

If you want to mobilize some mass social chaos capable of not only toppling a monarch but utterly replacing him with an entirely new political system... just throw some vocal ideology in there with skyrocketing food prices. Or wipe out the harvests one year. These things invariably lead to the kind of suffering that people just can't endure in silence.

And now I am thinking of a group of PC bastards who engineer a famine just so that they can topple a king. Does that make me a bad person?

ReplyDeleteOr maybe that can be a villain's plan in my Honor+Intrigue game. I think I can use that idea.

This is the very same plan undertaken by Marc Antony to topple Octavian when he captured Egypt: taking away the grain that fed Rome and kept its indigent citizens on the Dole was a clever move that never quite panned out for him.

DeleteI'll have to look and see who else engineered famines. I have a sneaking suspicion that attacking food supplies was rather common as a means to institute regime change. In fact, the chevauchee (the standard military maneuver of the 100 Years War) generally involved burning as many fields as possible and killing lots of peasantry to make them unhappy.

Strange how the Russians managed to accomplish the reverse of this during the Napoleonic invasion.